Meet the Artists: Nicholas Galanin

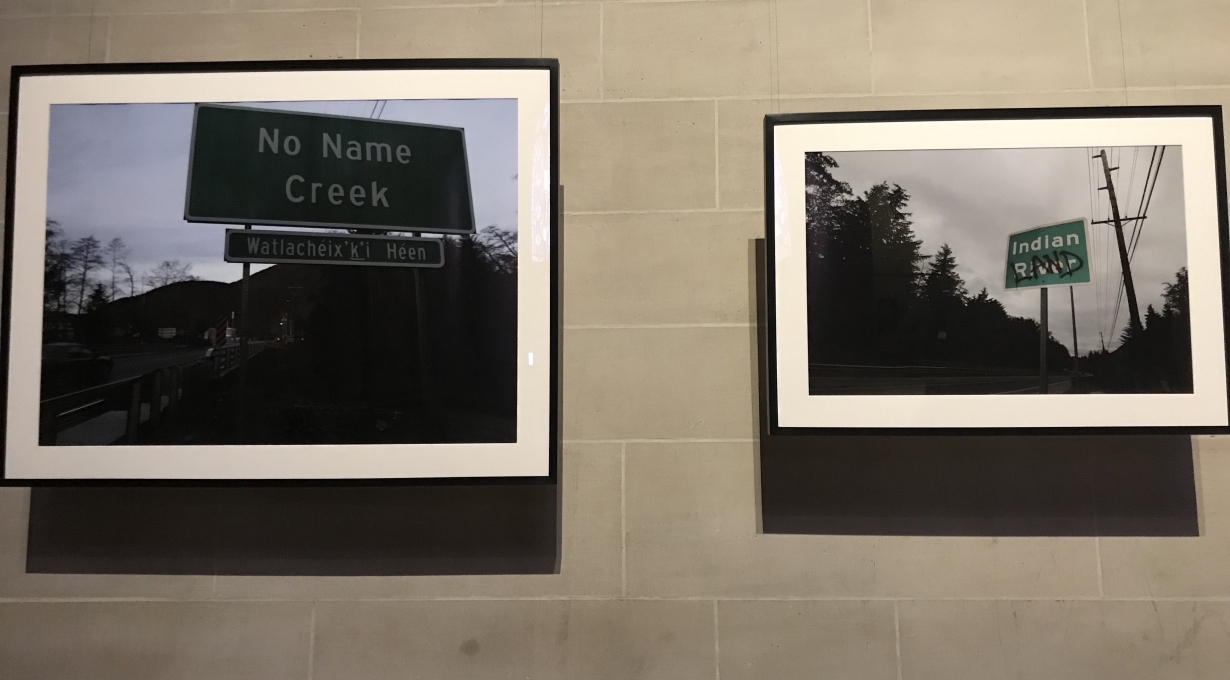

Nicholas Galanin's Your Inane Perspective: Haa Aaní Haa Kusteeyíx̱ Sitee (Our Land is Our Life) and Get Comfortable appear in the Value of Sanctuary: Building a House Without Walls, now on view in the Cathedral.

You can follow Nicholas on Twitter.

Editor's note: Capitalization has been left as written by the artist.

What were you thinking about when creating this piece of work? Had you spent any time considering the word “sanctuary”?

The photograph Get comfortable was shot in my home community. The altered sign spray focuses the viewer on LAND, a reminder that the land and people Indigenous to it remain connected regardless of the discomfort this may cause nations and communities built on colonial legacies of attempted genocide. The work raises questions about comfort, pointing to the lack of comfort afforded to Indigenous communities during the invasion of the Americas by colonial states and during the subsequent permanent settlement of the land. The title Get comfortable addresses communities that continue to disenfranchise and disregard Indigenous people, asserting the continued presence of Indigenous life connected to the land. Read by Indigenous communities, it is a reminder of presence as well, of comfort gained from land, of resistance to erasure, of responsibility to land. The work also acknowledges discomfort, a reminder that Indigenous communities have not been comfortable for generations; that cultural amnesia and cultural violence are maintained through the renaming of the land. By intervening actively, I encourage presence, resistance, and re-Indigenizing our concepts of place.

Haa Aaní (Our Land) recognizes Indigenous people’s relationship with land and animals that sustain human life as continually adjusting with technology. The carving of this rifle relates back to the oldest carved Tlingit fish clubs; honoring the animals who leave this life so that others will continue to live. The adoption of non-Indigenous technologies into Indigenous epistemologies is evidenced through incising Tlingit visual language into the rifle’s surface, claiming it as a Tlingit tool for subsistence.

What does it mean to you and/or the piece of art to be shown in a place of worship?

Can we sage smudge the space? This is a heavy contrast to the foundations of my culture and work, based on Indigenous relationship to place, Indigenous land which our communities have known and survived on and with since time immemorial. Manifest Destiny, driven often by the false doctrine that a certain god has justified genocide towards Indigenous communities in order to settle violently is highlighted in this particular installation. The fact that my generation is still here and continues to practice our culture is resilience.

What were your first impressions of the Cathedral?

I had never been in, so I had no expectations, much larger then I could imagine. I'm just a Merciless Indian Savage so it was also great to see my work placed in context and next to the window that celebrates the declaration of independence.

What is your favorite unexpected place to view art?

We are surrounded by art, as humans it is our beauty.

What artists or artworks are you inspired by?

In this exhibition, Mark Dukes work, Our Lady of Ferguson and All Those Killed by Gun Violence. It is a beautiful installation in the space and unfortunately relevant in today’s society.

Outside of the exhibition, I am inspired by so many creative artists and peers. All my collaborators in the Black Constellation: Nep Sidhu, Shabazz Palaces, Maikoiyo Alley-Barnes, and my partner Merritt Johnson's work; my father Dave Galanin and uncle Will Burkhart; James Luna; Shan Goshorn; and so many Indigenous artists making important work today; Raven Chacon.... the list goes on. What a time to be alive.

What is your Sanctuary?

My family, my children, the land and the sea, music & the studio. This is love.