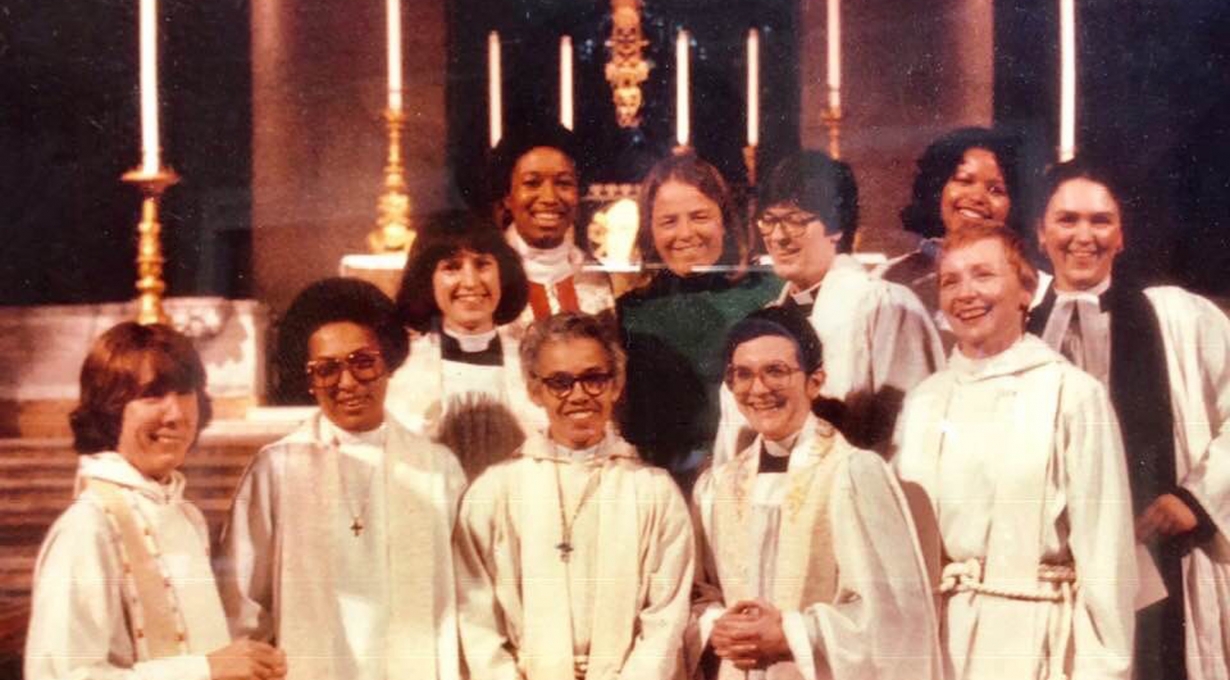

Celebrating the Rev. Pauli Murray

Activist, lawyer, teacher, author, priest. Anna Pauline “Pauli” Murray (1910-1985) took on many roles during her lifetime, the last of which was as the first African-American woman to be ordained an Episcopal priest. She is pictured here, bottom center, at the ordination of the Rev. Sandye Wilson at the Cathedral in 1982. (Photo courtesy of the Rev. Sandye Wilson.) Murray was included in the Calendar of Saints of The Episcopal Church in 2018 and is celebrated on July 1st.

Born in 1910 and raised in segregated North Carolina from a young age, Pauli Murray was a force to be reckoned with. She taught herself to read at age 5, graduated high school at 15, and moved to New York City to attend college. Having no interest in continuing her experience with “separate but equal” education, Murray enrolled in Hunter College after being rejected from Columbia University on the basis of her gender. She rented a room at the Harlem YWCA and worked multiple jobs to support herself through school as the United States entered the Great Depression and she was able to graduate in 1933.

Feeling inspired but frustrated by struggles for equal rights all around her, Murray applied to attend graduate school at the University of North Carolina but was rejected in a letter stating, “members of your race are not admitted.” Murray was furious and wrote to President Franklin D. Roosevelt and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt. Eleanor Roosevelt wrote back, regretted being unable to help, but encouraged Murray to keep fighting. The two were friends and pen pals for decades. Undeterred by the barriers ahead of her, Murray applied to Howard University Law School in 1941 and was accepted as the only woman in her class. She experienced frequent sexism at Howard University, and was appalled to discover: “men I deeply admired because of their dedication to civil rights...could countenance exclusion of women [and this] aroused an incipient feminism in me long before I knew the meaning of the term ‘feminism.’”

Murray graduated from Howard University in 1945, and the next 40 years of her life were dedicated to activism for civil rights and women’s rights. She worked as the Deputy Attorney General of California (the first African American to hold that title in the state), wrote books like States’ Laws on Race and Color that explained the complexities of legal segregation (which became Thurgood Marshall’s main reference book while arguing before the Supreme Court with Brown v. Board of Education), and founded the National Organization for Women with Betty Friedan in 1966.

Throughout her time as a lawyer and activist, Murray strained against the separation between civil rights for African Americans and women’s rights. As the civil rights movement was sidelining women, the women’s movement was sidelining minorities and the economically disenfranchised. In 1965, after being the first Black person to graduate with a doctorate in judicial science from Yale Law School, Murray co-wrote Jane Crow and the Law: Sex Discrimination and Title VII. In it, she described how racial segregation and gender segregation were more similar than people realized. Jane Crow would go on to be used by a young lawyer named Ruth Bader Ginsburg, who argued in Reed v. Reed (1971) that the Equal Protections Clause of the 14th Amendment should be applied to sex discrimination as well. Murray’s lifetime of work as an activist was able to argue for intersectionality between social justice movements long before the term “intersectionality” was present in our nation’s vernacular.

Murray’s time with The Episcopal Church came late in her life. At the age of 63 and after the death of a woman Murray spent much of her adult life with, Murray enrolled in seminary, and in 1977 she was ordained as the first African-American female priest in The Episcopal Church. She was in the first generation of female priests ordained, and one month after her vestment Murray administered her first Eucharist at the Chapel of the Cross – the small church in North Carolina where, more than a century earlier, a priest had baptized her grandmother Cornelia, an enslaved infant. Murray spent the last seven years of her life serving her community in a different, although equally meaningful, capacity as a priest. She died on July 1, 1985.

In 1970, Murray wrote: “If anyone should ask a Negro woman in America what has been her greatest achievement, her honest answer would be, ‘I survived!’” Murray expressed that she hadn’t accomplished all that she might have in a more egalitarian society, but without her service as an activist, lawyer, teacher, author, and priest, the civil-rights and women’s-rights movements that continue today would have been without a foundational leader.

Note: Recent scholarship suggests that Murray explored gender fluidity during her lifetime, and in private may have identified as a man, but because she self-identified as a woman in public, this post follows Murray’s lead and uses she/her language.